Full Length Research Article

The Clinical Significance of Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerization Domain-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 Inflammasome for the Health of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients

Sarah Ibrahim Dhaidan1*, Batool Hassan Al-Ghurabi2, Raja Hadi Al-Jubouri3, Osama Saad Madhloom4

Adv. life sci., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 583-588, August 2025

*- Corresponding Author: Sarah Ibrahim Dhaidan (Email: sarahibrahem239@gmail.com)

Authors' Affiliations

2. Department of Basic Science College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq.

3. Al-Turath University College, Baghdad, Iraq.

4. Al-Yarmouk Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

[Date Received: 14/12/2024; Date Revised: 04/02/2025; Available Online: 31/10/2025]

Abstract![]()

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

References

Abstract

Background: A recurring autoimmune disease with severe inflammation and joint destruction resulting from an immune-mediated inflammatory reaction is of concern these days, known as Rheumatoid arthritis (RA). It induces intracellular multi-protein signaling hubs, or inflammasomes, linked to pathogen sensing and triggering inflammatory processes in healthy and sick individuals. The Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) protein forms an inflammasome complex that regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production, including interleukin-1Beta and 18. Nowadays, numerous experimental agents have been studied for investigating various approaches to improve rheumatoid arthritis treatment, including pyrin domain-containing protein 3 inhibitors.

Methods: The current case-control experimental work involved 82 subjects separated into 3 groups: 22 patients were newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, 30 rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate (MTX), and 30 healthy subjects. The samples of saliva were obtained from all specimens, and the salivary inflammasome levels (NLRP3) were detected using ELISA.

Results: The study discovered a significant increase in salivary pyrin domain-containing 3 in patient groups in comparison with the healthy group (control). However, the results discovered that no noteworthy variance (p>0.05) was observed in salivary NLRP3 level between the newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis group and the rheumatoid arthritis patients in the methotrexate treatment group.

Conclusion: The study suggested that the elevated level of NLRP3 has a significant impact on disease etiology and could be used as diagnostic biomarkers for rheumatoid arthritis, and could be targeted for the treatment of RA by developing novel and beneficial agents.

Keywords: NLRP3, Inflammasomes, Rheumatoid arthritis, MTX

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, symmetrical inflammation of joints, causing cartilage and bone deterioration, resulting in bone weakness [1]. Initially, some bone joints are afflicted; however, as the condition progresses, more joints are damaged, and extra-articular symptoms are frequently observed [2]. A study conducted in Iraq found that females had greater incidences of RA than males [3].

Rheumatoid arthritis, early and later, poorly managed stages vary clinically. Exhaustion, sore and swollen joints, and morning stiffness are common symptoms of early-stage rheumatoid arthritis (RA), along with high CRP and ESR [4]. RA is linked to hyper-gammaglobulinemia and higher levels of acute-phase proteins. The synovial membrane contains mononuclear cells, which are then stimulated by T lymphocytes to aid B cells in producing rheumatoid factor [5]. However, inadequately treated rheumatoid arthritis demonstrated a complicated feature, including the emergence of systemic manifestations like lung nodules and pleural effusions, vasculitis, lymphomas, keratoconjunctivitis, atherosclerosis, and hematologic abnormalities, rheumatic nodules, cartilage degeneration, bone erosion, decreased range of motion, and joint malalignment are some symptoms. These systemic symptoms in RA patients of the prolonged inflammation pave the way for an increased mortality when they are all considered together [1,2,6].

Still, the most accurate and sensitive methods for diagnosing RA include clinical examination and history. It is crucial to understand that all currently used criteria for rheumatic disorders are classification criteria rather than diagnostic criteria, which creates a significant challenge in the diagnosis of RA [7].

The ACR and EULAR redefined rheumatoid arthritis classification in 2010 to emphasize early illness, autoantibody levels, ESR/CRP, and other immune activation and inflammatory markers [8]. Disease activity score 28 includes sore joints, swollen joints, the ESR, and the patient’s overall evaluation score [9-11]. The ACR approved utilizing the DAS28 as an outcome measure for nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic medication therapy in RA in 2008 [12]. A number of clinical trials using the DAS and DAS28 demonstrated the advantages of strict control in the management of RA [13-15]. The DAS28 assesses 28 sensitive joints (0-28), 28 swollen joints (0-28), a patient’s overall rating on a visual analogue scale (0-100), and ESR. Similar to the original DAS [11]. There are three categories that are used to categorize the degrees of disease activity. Some of these categories are low (DAS28 ≤3.2), moderate (3.2 < DAS28 ≤5.1), and severe (DAS28 > 5.1) [16].

Within roughly six months, the objective of therapy is to achieve full reduction or at least a significant decline in the illness, likewise to put an end to the degeneration of joints, disability, and systemic indications of rheumatoid arthritis [6,17]. With statistics standing at ’40% of patients with work disability after 10 years from onset and 80% of improperly treated patients with joint misalignment,’ it’s no wonder that early and intensive rheumatoid arthritis therapy is a priority [6,18,19]. RA treatments have improved over the last 30 years because of new drugs. DMARDs, immunosuppressive glucocorticoids, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications are available [20].

Aspirin, diclofenac, and ibuprofen are NSAIDs that are effective in reducing pain and swelling and enhancing joint function. However, as they cannot prevent further joint damage, they are not disease-modifying medications [1]. Prednisolone and other glucocorticoids are extremely effective anti-inflammatory medications that slow the radiologic progression by suppressing the expression of inflammatory genes in the early stages of disease [2,21].

Finally, DMARDs are medications employed to reduce rheumatoid inflammation and prevent subsequent destruction of the joints. Furthermore, these medications mitigate the manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis, improve physical functionality, and inhibit the progression of structural joint degradation [1,6]. There are three categories of DMARDs: conventional synthetic (methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine), targeted synthetic (pan-JAK and JAK1/2 inhibitors), and biologic (TNF-α inhibitors, TNF-receptor inhibitors, IL-6 inhibitors, IL-6 receptor inhibitors, co-stimulatory molecule inhibitors, B cell-depleting antibodies). Animal models are used to test numerous rheumatoid arthritis treatments. This includes mesenchymal stem cells, LRR, NOD, and NLRP3 inhibitors, and GM-CSF receptor, GM-CSF, or Toll-like receptor targeting [20].

The NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) protein can lead to inflammasome complexes that produce IL-1β in response to signals of danger [22]. NLRP3 inflammasome Components have been expressed in synovia of RA patients [23]. It was discovered that "inflammasome activation may be implicated in secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and that inflammasome inhibition may be a useful therapeutic strategy in future RA therapy". RA patients' synovia and an in vivo collagen-induced arthritis animal model show high NLRP3 inflammasome activity, according to Guo et al., [24]. Administration with MCC950, a “specific NLRP3 inhibitor,” resulted in a remarkable reduction in in vivo joint inflammation, bone erosion, and IL-1β production [25].

Inflammasomes were first defined as multiprotein platforms by Martinon et al., [26]. Their development is facilitated by organisms in response to different physiological and pathogenic conditions. These oligomeric protein complexes have distinct activation and regulation processes and can respond to a range of ligands. Inflammation is an immunological reaction to external pathogens and self-damage. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) identify PAMPs and DAMPs well [27]. NOD-like receptors are a class of NLRs that belong to the PRRs [28]. The most extensively researched receptor is NLRP3, which belongs to the family of NOD-like receptors. According to Mangan et al., [29], NLRP3 is created and activated when it identifies invading pathogens and self-danger signals [22]. NLRP3 is a PRR critical to innate immunity and inflammation. Inflammasome NLRP3 detects bacteria, viruses, and tissue injury. Activating caspase-1 by NLRP3 inflammasome causes pyroptosis and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, thereby augmenting inflammation [30]. The inflammatory reactions triggered by the NLRP3 inflammasome’s mild activation can rapidly and efficiently eradicate microbial infections and restore damaged tissue. However, excessive NLRP3 inflammasome activation causes unwanted host damage, excessive inflammation, and a pathological condition in the body [31]. Initiating adaptive immunological responses is another crucial function of innate immunity, which enables the host to establish long-lasting, efficient defenses. As a result, adaptive immunity is a consequent expansion of innate immunity [32]. Additionally, adaptive immunity needs the NLRP3 inflammasome. NLRP3 activation is essential for IL-1β and IL-18 production. IL-18 modulates inflammatory and immune responses and is a sensitive inflammation biomarker [33]. Naive T cells can be stimulated to differentiate between memory T cells and effector T cells by the cytokines produced by these two pro-inflammatory cytokines, which will activate adaptive immunity [34]. This study aims to explore NLRP3's involvement in rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis.

This case-control research had 82 participants categorized into three groups: 22 individuals newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, 30 patients with rheumatoid arthritis on methotrexate treatment, and 30 ostensibly healthy individuals. Each candidate in the patient group received a DAS 28 disease activity score, the Rheumatologist's disease activity assessment. The College of Dentistry/University of Baghdad Ethical Review Board approved this study project (Ref. No. 465, January 2022). Participants in this study had to meet the 2010 ACR/EULAR inclusion criteria, be older than 20 years and not have any infectious diseases like hepatitis, malignancies, cardiovascular complications, or other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases. Saliva from each subject was collected, and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure salivary concentrations of inflammasome NLRP3.

Sample size calculation:

The G power 3.1.9.7 analysis tool was used to calculate the size of the sample with a power of research of 95% and an alpha error of 0.05 on a two-sided scale [35].

Estimation of DAS28:

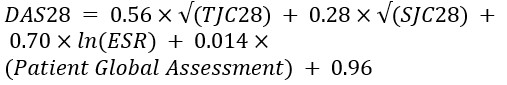

According to DAS 28, each candidate in the patient group received a score for disease activity. This index includes three measurements: an ESR measure (as a marker of inflammation), a TJC (tender joint count) range of 0-28, and an SJC (swollen joint count) range of 0-28. The following equation was used for calculating DAS28:

Saliva Samples Collection:

All subjects fasted for an hour as per instructions, sat comfortably, and saliva samples visibly contaminated with blood were discarded. The participants were also instructed to sit comfortably. The saliva was obtained between 9 and 12 that morning. After cleaning their mouth with sterile water for one to two minutes, polyethylene tubes were used to collect up to 5 ml of unstimulated saliva. Saliva was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm and stored in Eppendorf tubes at -20 °C.

Measurement of Salivary Biomarkers:

The ELISA kit (Shanghai/China) was used to measure the concentration of the NLRP3 protein.

Statistical analysis:

The SPSS version 24 statistical software suite was used. Differences between groups were assessed using an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. The Pearson correlation coefficient test determined factor associations. Significant P-values are 0.05 or below.

ESR-based disease activity score 28 (DAS 28) estimation

This study found a non-significant difference (p>0.05) in mean DAS-28 scores between two RA patient groups upon diagnosis. The mean DAS-28 score for the RA patients receiving MTX was (5.04±0.71), while the newly diagnosed RA group had a mean score of (4.83 ± 1.07), as illustrated in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Salivary NLRP3 Level

The current study noticed a highly significant increase in salivary NLRP3 (P˂0.05) among patient groups in comparison with the control group, as clearly shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. Compared to the control, NLRP3 levels were significantly increased in both the MTX therapy and newly diagnosed RA groups. Salivary NLRP3 levels were not, however, significantly different (p>0.05) between these two groups of patients, as in Table 3.

Figures & Tables

Due to the fact that RA leads to joint inflammation, resulting in joint damage and decreased function, it is vital to evaluate the severity of RA clinically so that the efficacy of current treatment methods can be determined, and whether moving to other medications is necessary [36]. Vis-à-vis disease activity during initial diagnosis of RA, the DAS-28 value for the group recently diagnosed with RA was close to that reported by Smigielska-Czepiel et al., [37] and lower than that reported by Li et al., [38]. The DAS-28 value in the group of RA patients on MTX was comparable to that reported by Filková et al., [39] and Hruskova et al., [40], as well as the mean DAS-28 value in an Iraqi study on RA conducted by Khidhiret et al., [41].

The present study showed an increase in the salivary NLRP3 level in RA patient group compared with control subjects, and it is consistent with several studies that demonstrated that NLRP3 mRNA and NLRP3 inflammasome-related proteins are upregulated in monocytes, macrophages, and DCs of patients with RA [42,43]. The current results align with Choulaki et al., [44], who reported that patients with active RA exhibit heightened expression of NLRP3 and NLRP3-mediated IL-1β secretion in whole blood cells [44]. NLRP3 is raised in the synovial tissue, whole blood, and CD4 T lymphocytes of individuals with active RA [42]. Ramos-Bello et al., [45] in a trial to evaluate the possible effect of MTX and MTX plus Colchicine (CCH) in NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activity in early RA patients, indicated that caspase-1 activity and NLRP3 expression were raised in all patients; patients in MTX had a modification in its expression in month one, but that difference was not subsequently identified in month three [45].

In comparison, patients with MTX + CCH had significantly lower NLRP3 expression and activity at first and third months. Clinical indicators also improved significantly in the first and third months. CCH treatment reduced NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activity, suggesting that CCH is a powerful NLRP3 inhibitor [45].

These results are in agreement with a study that investigated the correlation between the SNPs in NLRP3 gene and the vulnerability to RA in the Han Chinese population. The study demonstrated that the expression of NLRP3 in neutrophils and Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) was correlated significantly with DAS28, CRP, and ESR [46].

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all participants in the present study.

Author Contributions

Sarah Ibrahim Dhaidan: Conceptualization, study design, data collection, manuscript drafting, and final approval of the manuscript.

Batool Hassan Al-Ghurabi: Reviewing and supervision.

Raja Hadi Al-Jubouri: Manuscript review and supervision.

Osama Saad Madhloom: Technical support, manuscript editing.

The authors state that there is no conflict of interest in the publishing of this work.![]()

References

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet, (2016); 388(10055): 2023–2038.

- Littlejohn EA, Monrad SU. Early diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, (2018); 45(2): 237–255.

- Taha GI, Talib EQ, Abed FB, Hasan IA. A review of microbial pathogens and diagnostic techniques in children’s oral health. Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health, (2024); 53(4): 355–359.

- Brzustewicz E, Henc I, Daca A, Szarecka M, Sochocka-Bykowska M, et al. Autoantibodies, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serum cytokine profiling in monitoring of early treatment. Central European Journal of Immunology, (2017); 3(2017): 259–268.

- Subhi IM, Zgair AK. Estimation of levels of interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-10 in sera of some Iraqi patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Iraqi Journal of Science, (2018); 59(3C): 1554–1559.

- Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA, (2018); 320(13): 1360-1372.

- Studenic P, Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Discrepancies between patients and physicians in their perceptions of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis & Rheumatism, (2012); 64(9): 2814–2823.

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis & rheumatism, (2010); 62(9): 2569–2581.

- Talib EQ, Taha GI. Involvement of interleukin-17A (IL-17A) gene polymorphism and interleukin-23 (IL-23) level in the development of peri-implantitis. BDJ Open, (2024); 10(1): 12.

- Prevoo MLL, Van’T Hof MA, Kuper HH, Van Leeuwen MA, Van De Putte LBA, et al. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts: Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, (1995); 38(1): 44–48.

- van der Heijde DM, van ’t Hof MA, van Riel PL, Theunisse LA, Lubberts EW, et al. Judging disease activity in clinical practice in rheumatoid arthritis: First step in the development of a disease activity score. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, (1990); 49(11): 916–920.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, (2008); 59(6): 762–784.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Kerstens PJSM, Nielen MMJ, Vos K, et al. DAS-driven therapy versus routine care in patients with recent-onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, (2010); 69(1): 65–69.

- Fransen J, Moens HB, Speyer I, Van Riel PL. Effectiveness of systematic monitoring of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in daily practice: A multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, (2005); 64(9): 1294–1298.

- Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, McMahon AD, Lock P, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): A single-blind randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, (2004); 364(9430): 263–269.

- van Gestel AM, Haagsma CJ, van Riel PL. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis improvement criteria that include simplified joint counts. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, (1998); 41(10): 1845–1850.

- Burmester GR, Pope JE. Novel treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet, (2017); 389(10086): 2338–2348.

- Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Möttönen T, Hannonen P. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis 10 years after the diagnosis. The Journal of rheumatology, (1999); 26(8): 1681–1685.

- Wolfe F. The natural history of rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of rheumatology, (1996); 44(1996): 13–22.

- Lin YJ, Anzaghe M, Schülke S. Update on the pathomechanism, diagnosis, and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis. Cells, (2020); 9(4): 880.

- Taha GI. Involvement of IL-10 gene polymorphism (rs1800896) and IL-10 level in the development of peri-implantitis. Minerva Dental and Oral Science, (2024); 73(5): 264–271.

- Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nature Reviews Immunology, (2019); 19(8): 477–489.

- Kolly L, Busso N, Palmer G, Talabot-Ayer D, Chobaz V, et al. Expression and function of the NALP3 inflammasome in rheumatoid synovium. Immunology, (2010); 129(2): 178–185.

- Guo C, Fu R, Wang S, Huang Y, Li X, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, (2018); 194(2): 231–243.

- Williamson DJ, Begley CG, Vadas MA, Metcalf D. The detection and initial characterization of colony-stimulating factors in synovial fluid. Clinical and experimental immunology, (1988); 72(1): 67–73.

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-β. Molecular cell, (2002); 10(2): 417–426.

- Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell, (2010); 140(6): 805–820.

- Kim YK, Shin JS, Nahm MH. NOD-like receptors in infection, immunity, and diseases. Yonsei medical journal, (2016); 57(1): 5-14.

- Mangan MSJ, Olhava EJ, Roush WR, Seidel HM, Glick GD, et al. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nature reviews Drug discovery, (2018); 17(8): 588–606.

- de Torre-Minguela C, Mesa del Castillo P, Pelegrín P. The NLRP3 and Pyrin inflammasomes: Implications in the pathophysiology of autoinflammatory diseases. Frontiers in immunology, (2017); 8(2017): 1-17.

- He Y, Hara H, Núñez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends in biochemical sciences, (2016); 41(12): 1012–1021.

- Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nature immunology, (2015); 16(4): 343–352.

- Al Obaidi MJ, Al Ghurabi BH. Potential role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the pathogenesis of periodontitis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Medicinal and Chemical Sciences, (2023); 6(3): 522-531.

- Evavold CL, Kagan JC. How inflammasomes inform adaptive immunity. Journal of molecular biology, (2018); 430(2): 217–237.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 1988: 75-108. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers

- Aletaha D, Ward MM, Machold KP, Nell VPK, Stamm T, et al. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: Defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis & Rheumatism, (2005); 52(9): 2625–2636.

- Smigielska-Czepiel K, van den Berg A, Jellema P, van der Lei RJ, Bijzet J, et al. Comprehensive analysis of miRNA expression in T-cell subsets of rheumatoid arthritis patients reveals defined signatures of naive and memory Tregs. Genes & Immunity, (2014); 15(2): 115–125.

- Li J, Wan Y, Guo Q, Zou L, Zhang J, et al. Altered microRNA expression profile with miR-146a upregulation in CD4+ T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy, (2010); 12(3): 1-12.

- Filková M, Aradi B, Šenolt L, Ospelt C, Vettori S, et al. Association of circulating miR-223 and miR-16 with disease activity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, (2014); 73(10): 1898–1904.

- Hruskova V, Jandova R, Vernerova L, Mann H, Pecha O, et al. MicroRNA-125b: Association with disease activity and the treatment response of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy, (2016); 18(1): 1-8.

- Khidhir RM, Al-Jubouri RH. The study of temporomandibular joint disorders and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in serum and saliva of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Baghdad College of Dentistry, (2013); 25(Special Issue): 67–71.

- Guo C, Fu R, Wang S, Huang Y, Li X, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, (2018); 194(2): 231–243.

- Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P, Liakouli V, Berardicurti O, et al. Monocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus display an increased production of interleukin (IL)-1β via the nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing family pyrin 3 (NLRP3)-inflammasome activation: A possible implication for therapeutic decision in these patients. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, (2015); 182(1): 35–44.

- Choulaki C, Papadaki G, Repa A, Kampouraki E, Kambas K, et al. Enhanced activity of NLRP3 inflammasome in peripheral blood cells of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy, (2015); 17(1): 1-11.

- Ramos-Bello D, Alvarez-Quiroga C, Aguilera Barragan-Pickens G, Pedro Martinez AJ, Adriana Luna-Zuniga T, et al. Effect of Methotrexate (MTX), and MTX Plus Colchicine (CCH) on the Expression and Activity of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Patients with Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA); 2017. WILEY 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA. pp. 1979-1980.

- Cheng L, Liang X, Qian L, Luo C, Li D. NLRP3 gene polymorphisms and expression in rheumatoid arthritis. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, (2021); 22(4): 1110.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. To read the copy of this license please visit: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0